A Path to Services - Part 3 - Synchronous Events

This article was originally posted on the PipelineDeals Engineering Blog

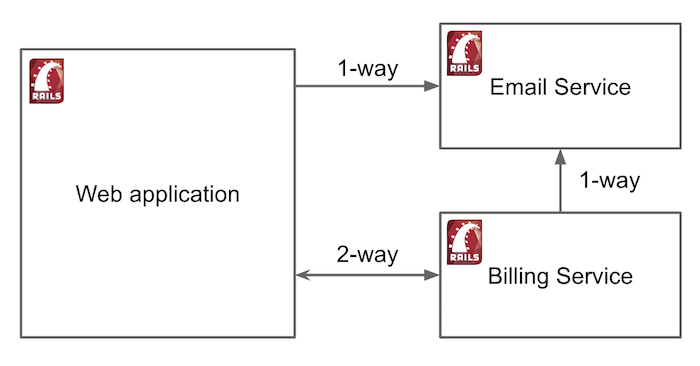

In the previous article in this series, we introduced a billing service to determine which features an account could access. If you remember, the email service was a “fire and forget” operation and was capable of handling throughput delays given its low value to the core application.

This post will explore how we handle synchronous communication for a service like billing where an inline response is required to service a request from the core application.

Background

If you remember from the previous post, we introduced the billing service to an infrastructure that looked like this:

Handling multiple pricing tiers in a SaaS app means you have to control authorization based on account status. Our billing service encapsulates the knowledge of which features correspond to which pricing tier.

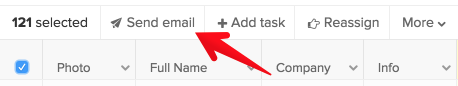

For instance, one feature is the ability to send trackable email to contacts in your PipelineDeals account. To service this request, we add an option to the bulk action menu from a list view:

Service Request

Before we can conditionally show this option based on the pricing tier, we have to first make a request to the billing service to get the list of features available to that user.

class Billing::Features

def initialize(user)

@user = user

@account = user.account

end

def list

Rails.cache.fetch("account_#{account.id}_billing_features") do

response = Billing::Api.get "account/#{account.id}/features"

response['features']

end

end

private

attr_reader :user, :account

endBilling::Api, in this case, is a wrapper around the API calls to handle exceptions and other information like security.

Note: When making synchronous HTTP calls like this, it’s worth considering the failure state and providing a default response set in that case so the user isn’t burdened with a failure page. In this case, one option would be dumb down the features on the page to the most basic tier.

Serving a JSON API

Plenty of articles have been written about how to create a JSON API with Rails, so we won’t rehash those techniques here. Instead, we’ll highlight patterns we’ve used for consistency.

We tend to reserve the root URL namespace for UI-related routes, so we start by creating a unique namespace for the API:

namespace :api do

resources :account do

resource :features, only: :show

end

endThis setup gives us the path /api/account/:account_id/features. We haven’t found a need for versioning internal APIs. If we decided to in the future, we could always add the API version as a request header.

The features endpoint looks like:

class Api::FeaturesController < Api::ApiController

skip_before_filter :verify_authenticity_token

def show

render json: {

success: true,

features: AccountFeatures.new(@account_id).list

}

end

endNotice Api::FeaturesController inherits from Api::ApiController. We keep the API-related functionality in this base controller so each endpoint will get access to security and response handling commonalities.

AccountFeatures is a PORO that knows how to list billing features for a particular account. We could’ve queried it straight from an ActiveRecord-based model, but our handling of features is a little more complicated than picking them straight from the database.

Another note here is that we haven’t introduced a serializing library like active_model_serializers or jbuilder. Using render json alone has serviced us well for simple APIs. We reach for something more complex when the response has more attributes than shown above.

Handling Service Response

By introducing Rails.cache, we can serve requests (after the initial) without requiring a call to the billing service.

One of the first things we do is serialize the set of features to JavaScript so our client-side code has access:

<%= javascript_tag do %>

window.Features = <%= Billing::Features.new(logged_in_user).list.to_json %>;

<% end %>We also include a helper module in to our Rails views/controllers, so we can handle conditional feature logic:

module Features

def feature_enabled?(feature)

Billing::Features.new(logged_in_user).list.include?(feature.to_s)

end

endSynchronous Side Effects

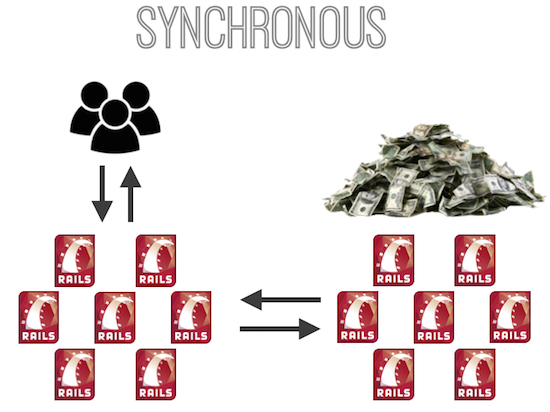

When we looked at asynchronous service requests, there was less immediacy associated with the request due to its “fire-and-forget” nature. A synchronous request, on the other hand, will handle all requests to the core application, so scaling can be challenge and infrastructure costs can add up.

In addition to the infrastructure costs, performance can be a factor. If the original page response time was 100ms and we’re adding a synchronous service request that takes another 100ms, all of a sudden we’ve doubled our users’ response times. And while this architectural decision might seem like an optimization, I’m positive none of our users will thank us for making their page load times 2x slower.

Summary

As you can see, there’s little magic to setting up a synchronous service request.

Challenges appear when you consider failure states at every point in the service communication - the service could be down, or the HTTP request itself could fail due to network connectivity. As mentioned above, providing a default response during service failure is a great start to increasing the application’s reliability. Optionally, the circuit break pattern can provide robust handling of network failures.

Part 4 in this series will cover how we manage asynchronous communication between services, specifically around an open source gem we built called Mantle.